A little holiday detour here.

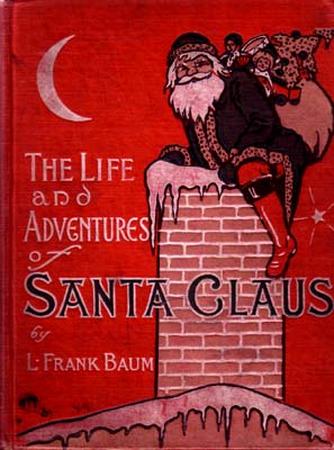

Never one to miss a commercial fantasy opportunity, in 1902 L. Frank Baum decided to write a book long tale explaining the origins and life of Santa Claus, a figure of growing popularity in the United States, thanks partly to the Clement Moore poem and to numerous depictions of the jolly old elf. In this relatively early work (after The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, but before the Oz sequels), Baum took a comparatively serious, explanatory tone, giving a feel quite different than most of his other works.

Set in some misty time long ago—before toys (which, technically, should probably be before the Cro-Magnon period, but Baum was never particular about minor historical details) but after Christmas, with certain decidedly medieval details (including a Baron) suggesting a time that can best be called “magical,” this is a tale of a man who is almost unbelievably good, and almost equally unbelievably and unabashedly secular for a folk figure so associated with a Christian holiday.

As with so many of Baum’s tales, Santa Claus starts in a land of fairies and immortals, who have just encountered a human baby. In the first of many attempts to distance the tale of Santa Claus from the legend of St. Nicholas, a nymph decides to name the baby “Neclaus,” which, as Baum engagingly explains, was later misunderstood as “Nicholas.” This name is later shortened to just Claus, as the baby ages rather rapidly by immortal standards and leaves the immortal forest for mortal lands.

Baum painstakingly explains nearly every detail of the Santa Claus legend: why children should hang up stockings (it saves Santa Claus time); the reindeer (ten in this version, as opposed to the eight in the Clement Moore version, and, of course, lacking Rudolph and the red nose); the chimneys (Santa is in a rush) the very anxious question of what happens if your house has only very skinny chimneys or worse, no chimneys at all because you have, gasp, put in a stove (no worries; fairies can do everything, including walking through walls); and just why no one can ever catch anything more than the merest glimpse of Santa. (Did we mention the rush? Santa’s VERY BUSY, everyone! Hang up that stocking carefully.)

Oh, and even the toys, which Claus invents one dull night, by carving a replica of his cat, an item he later gives to a delighted child. (As the pet of two cats, I was equally delighted with this detail, and by the irritated and offended response by the cat.) The tale also explains why both rich and poor children can expect Santa Claus (it’s not fair for rich children not to get toys, even if they already have ponies and servants, just because they are rich.)

And in a surprising touch, Baum rejects a center part of the Santa Claus legend:

And, afterward, when a child was naughty or disobedient, its mother would say:

“You must pray to the good Santa Claus for forgiveness. He does not like naughty children, and, unless you repent, he will bring you no more pretty toys.”

But Santa Claus himself would not have approved this speech. He brought toys to the children because they were little and helpless, and because he loved them. He knew that the best of children were sometimes naughty, and that the naughty ones were often good. It is the way with children, the world over, and he would not have changed their natures had he possessed the power to do so.

Highly reassuring to those of us who had thrown toys at small brothers and were in seemingly grave danger of losing our visits from Santa Claus as a result.

This is but one of the unabashedly secular points of the tale, which goes to great lengths to note that the decision by Santa Claus to deliver toys on Christmas Eve is purely coincidental and has nothing to do with the Christmas holiday; that parents, but not a church, named Claus “Santa,” after seeing him leave toys for the children and deciding that he must be good. Even more to the point, the story is set in a world ruled by various immortal beings who care for animals and plants and, yes, humans, beings that vaguely acknowledge a Supreme Master who was about at the very beginning of time, but who does not seem to be around much now.

Near the end of the tale, as Claus lies, dying of old age, these immortals gather to decide if they can give Santa Claus the cloak of immortality, an extraordinary gift that can be given to one, and only one, mortal:

“Until now no mortal has deserved it, but who among you dares deny that the good Claus deserves it?”

This would be less surprising in a tale not devoted to a supposedly Christmas legend: surely, much of the point of the Christian part of the holiday is that at least one mortal did deserve it. (Although I suppose the immediate counterargument is that particular mortal wasn’t actually or entirely mortal.)

But then again, the Santa Claus tale has had a decidedly pagan and secular tone to it, and Baum cannot be entirely blamed for following in this direction; he may even have felt it safer to downplay any Christian connections to the jolly saint.

He can, however, be blamed for writing an entire novel without much of a plot, or, worse, humor. Baum had written novels that were little more than loosely connected tales before this, but those had been leavened by jokes, puns, silliness, adventure and joy. This book has little adventure (Baum does tell of the difficulties between Claus and some rather nasty Awgwas, but as typical of Baum, the battle scenes are hurried over and poorly done, and although the battle is about Claus, he is barely involved.), few jokes, and a rather serious, explanatory tone throughout. And aside from the Awgwas and one Baron, nearly everyone in the book is painfully, oppressively good. This does not prevent the book from having many magical moments (although I am perhaps biased about the cat toy scene) but it does prevent the book from being as much fun as his other tales. And, like a couple of his other books, this is decidedly, in language and tone, a book for children. It is not a bad book to read to a child on a cold winter night, especially a child eager to learn about the fairies that help Santa make and deliver toys, but adults may not be as engaged. (Illustrated editions decidedly help.)

Nonetheless, Baum was fond enough of his characters to bring them back in cameo appearances in The Road to Oz and in their own tale, “A Kidnapped Santa Claus. ” Neither one of these was enough to prevent the book from falling into general obscurity for some time, although it is now widely and easily available on the internet in both online and print editions, with various illustrators doing some wonderfully inspired work for the book.

Regrettably enough, Mari Ness has now decided that she can safely be naughty this holiday season, which means more cookies. Perhaps this is not that regrettable. She wishes all of you the happiest of whatever holidays you may celebrate, and promises to return to the Maguire books shortly after this little Santa detour.